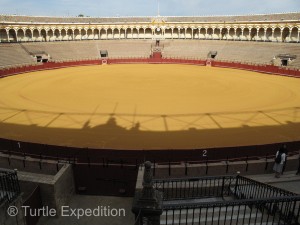

As a young boy living near Guadalajara, Mexico, bullfighting was one of those things kids played, like cowboys and Indians. Having been to several bullfights over the years, I’ve always been intrigued about where these specially bred bulls come from. Since Seville was one of the more important centers for bullfighting in Spain, a little research showed that some of the most famous fighting bulls were raised near a small town called Lora Del Rio. A little more detective work gave us the name of the ranch and its location.

The ranch originally belonged to Don Eduardo Miura Fernández, and is known for producing large and difficult fighting bulls. A Miura bull first debuted in Madrid on April 30, 1849. Bulls from the Miura lineage have a reputation for being large, fierce, and cunning. It is said to be especially dangerous for a matador to turn his back on a Miura. Miura bulls have been referred to as individualists, each bull seemingly possessing a strong personal character.

In his book Death in the Afternoon, Ernest Hemingway wrote:

There are certain strains of bulls with a marked ability to learn from what goes on in the arena … faster than the actual fight progresses which makes it more difficult from one minute to the next to control them … these bulls are raised by Don Eduardo Miura’s sons from old fighting stock…

Bulls often have names. One called Murciélago survived 24 jabs with the lance from the picador in a fight October 5, 1879 against Rafael “El Lagartijo” Molina Sanchez, at the Coso de los califas bullring in Córdoba, Spain. Murciélago fought with such passion and spirit that the crowd called for his life to be spared, an honor which the matador bestowed. The bull, which came from Joaquin del Val di Navarra’s farm, was later presented as a gift to Don Antonio Miura, Don Eduardo’s brother. The Miuras proceeded to sire him into the Miura line.

The name Miura is best known outside the world of bullfighting thanks to Ferruccio Lamborghini’s sports car company, Lamborghini, and its classic Miura sports car. A number of Lamborghini cars have been named for Miura bulls. It was a visit to the Miura ranch that inspired Ferruccio Lamborghini, a Taurus himself, to make a bull the symbol of his industrial empire.

Arriving at the Finca Zahariche, there was a very explicit sign next to the MIURA Ranch entry: GANADO BRAVO—PROHIBIDO ENTRAR “Brave Bulls–Do Not Enter”, so we drove by thinking “Oh well, we tried”. But not being one to take “no” for an answer, I asked a local guy on horseback about the situation. He said, “Don’t worry about the gate. You can go in. Just make sure you close it behind you.” Okay, so we did, and soon arrived at the beautiful ranch home of António Miura Martínez and his brother Eduardo.

After making friends with the dogs, we met Antonio in the courtyard and I explained my passion for bullfighting and wondered if we could even see some of his famous bulls. He said no problem and told us where a couple of fenced areas were where the bulls were hanging out. We learned that he raises about 60 bulls each year and supplies six bulls each to eight different bullfights in Spain. Some animals die each year in the field fighting each other or otherwise injuring themselves like breaking their horns off or poking their eyes out.

I did ask him if any of his bulls ever killed a matador. He smiled and said yes, a few. I responded by saying “Well, if the matador is killed, I guess it’s his fault.” Antonio quickly answered with a grin and said: “Absolutely not. If a matador is killed, it’s the bull’s fault. After all, that’s what they are raised to do, kill matadors. In the ring, as far as they know, they are fighting for their lives.”

I asked what he thought about the people who think the poor bulls are suffering and it is a cruel sport, he said the bulls probably suffer more just being carted up and transferred to the ring than they do in the fight. Occasionally, a bull is pardoned, like the one named Murciélago, but Antonio said none of his animals have ever come back.

We spent the afternoon watching bulls, shooting pictures, and in the evening, we ended up camping on a side road next to where they were grazing. Señor Miura had advised us to stay on the right side of the fence. The Bulls were not always dangerous but they have their tempers, and if you happen to catch one in a bad mood you better stay out of its way.

The explicit sign, GANADO BRAVO—PROHIBIDO ENTRADA “Brave Bulls–Do Not Enter” gave warning of what was inside.

“Listen Poncho, you get in my way, I poke your eye out.”

“Hey Ramon, I hear the cows in California are really cute, and they speak Spanish. Nicer than those snooty Swiss cows.”

“What are you staring at dude? You looking for trouble?”

OK José, I’ll take the guy with the camera. You get the girl.”

Some animals die each year in the field fighting each other or otherwise injuring themselves like breaking their horns off or poking their eyes out.

“You looking for trouble? I’m waiting for you.”

“So you thought all fighting bulls were black. Don’t make this your second mistake.”

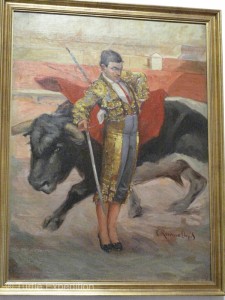

Matador El Fundi and a Miura bull are battling it out on a life and death stand-off. Feria de Abril, Seville, Spain, 2009. Photo by Alexander Fiske-Harrison

Eduardo Miura Martínez (L) and his brother António (R) were happy to talk about their famous Toros Bravos (fighting bulls) with Gary, (wannabe matador, Center).

We were careful to close the gate when we drove out of the Miura Ranch.

In the evening we camped on a side road and watched a small herd of bulls lazily grazing in the pasture.