Istanbul 5, Turkey – April 2014

After a quick Shish Kebab on the street and a glass of fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice, we headed over to the astounding and fascinating Topkapı Palace and museum, home of the Ottoman Sultans for nearly 400 years.

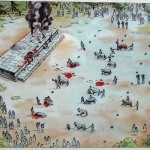

The Palace is an extensive complex rather than a single monolithic structure, with an assortment of low buildings constructed around courtyards, interconnected with galleries, passages and pavilions that stretch down the promontory towards the shores of the Bosporus. The total size of the complex varies from around 592,600 square meters (1,944,225 square feet) to 700,000 square meters (7,534,983 square feet), depending on which parts are counted. Don’t ask how many bathrooms. Many of the walls of the palace are ten feet thick, so it mostly escaped structural damage during the 1999 Izmit earthquake.

Checking the map in our Lonely Planet guide, we saw that there were four main courtyards, essentially beautiful parks with lush gardens and fountains. Clearly, we would need two days to see it all.

The palace kitchens alone consisted of 10 domed buildings. They were the largest kitchens in the Ottoman Empire with a staff of 800 to 1,000 people and the capacity to prepare up to 6,000 meals a day. We’re not talking about paper plates either. Chinese and Far Eastern porcelain was highly valued and was transported by camel caravans over the Silk Road or by sea. The 10,700 pieces of Chinese porcelain displayed are thought to rival that found in China as one of the finest collections in the world.

We didn’t want to miss the Harem. What’s a Harem? Among several definitions, it is a separate part of a Muslim household reserved for wives, concubines, and female servants. One might have a romantic image of beautiful girls, (concubines), skimpily dressed, parading around with their only job to please the master, like “Peel me a grape, honey.” In this case, being the home of the Sultan, Topkapı’s Harem had more than 400 rooms with hundreds of concubines, children, and servants. There were special rooms for the Queen Mother, the sultan’s consorts and “favorites”, the princes and the concubines as well as the eunuchs, both black and white, who had been castrated in order to make them reliable to serve the royal court. The “favorites” of the Sultan were conceived as the instruments of the perpetuation of the dynasty in the harem organization. When the “favorites” became pregnant they assumed the title and powers of the Official Consort of the Sultan. As it turns out, many of the women in the Sultan’s Harem had considerable political power.

We didn’t want to miss the Harem. What’s a Harem? Among several definitions, it is a separate part of a Muslim household reserved for wives, concubines, and female servants. One might have a romantic image of beautiful girls, (concubines), skimpily dressed, parading around with their only job to please the master, like “Peel me a grape, honey.” In this case, being the home of the Sultan, Topkapı’s Harem had more than 400 rooms with hundreds of concubines, children, and servants. There were special rooms for the Queen Mother, the sultan’s consorts and “favorites”, the princes and the concubines as well as the eunuchs, both black and white, who had been castrated in order to make them reliable to serve the royal court. The “favorites” of the Sultan were conceived as the instruments of the perpetuation of the dynasty in the harem organization. When the “favorites” became pregnant they assumed the title and powers of the Official Consort of the Sultan. As it turns out, many of the women in the Sultan’s Harem had considerable political power.

Recalling my first visit years ago as a neophyte traveler, I remember being astounded by the unimaginable wealth found in the Treasury. The Imperial Treasury is a vast collection of works of art, jewelry, heirlooms of sentimental value and money belonging to the Ottoman dynasty. Many are of solid gold and other precious materials and covered with diamonds, emeralds and rubies. I recall two enormous solid gold candleholders, each weighing 48 kg, (105 lbs), and mounted with 6,666 cut diamonds. The Imperial Treasury is without doubt one of the world’s greatest treasure chambers.

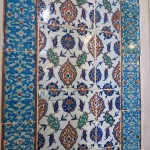

Every room we entered had amazing detailed paintings, rare woods inlayed with mother of pearl, beautiful tiles, intricate mosaics. The whole Topkapı Palace and museum is just something you have to see to comprehend. The obvious wealth of the Sultans puts Donald Trump to shame.

- Checking the map of our Lonely Planet guide, clearly we would need two days to see all of Topkapı Palace.

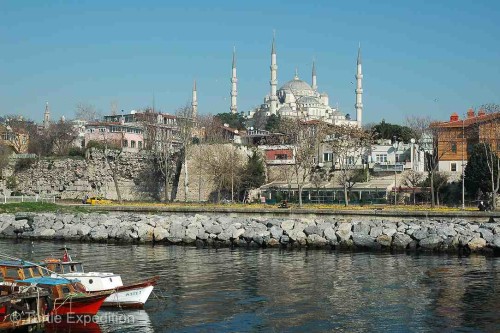

- The spacious 7,534,983-sft. Topkapı Palace can only be seen in its entirety from the Bosporus. Photo by Carlos Delgado

- There were four main courtyards, essentially beautiful parks with lush gardens and fountains.

- This ancient tree provided shade for the visitors.

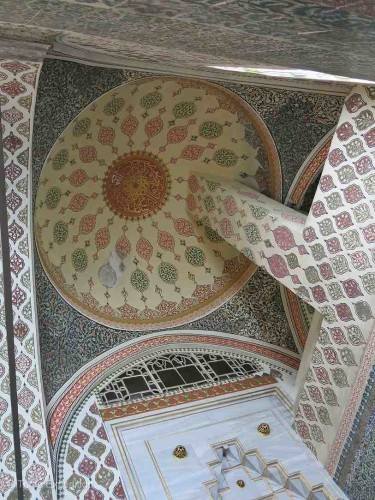

- The intricate design of the palace roofs showed amazing craftsmanship.

- Many of the special sections of the palace had ornate entrances.

- Intricate inlaid walkways showed the tedious details the artists were capable of.

- Throughout the palace there were many beautiful washing fountains.

- This gilded mirror was at the entrance to the Harem.

- This closet door had clearly been influenced by the art of Western Europe.

- The doors to this cupboard were a great example of the intricate inlay of mother of pearl.

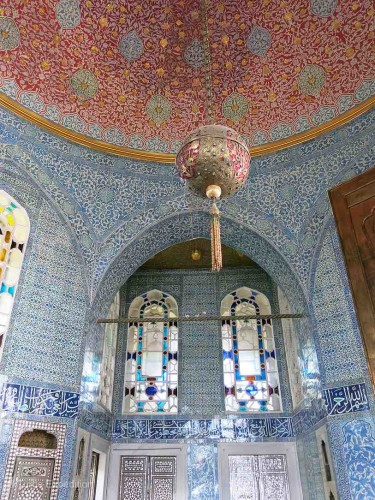

- Throughout the palace every room seemed to have new and more beautiful dome.

- Examples of Isnik tile could be found throughout the palace.

- This small room with mannequins showed the lifestyle and dress of the black Eunuchs, servants in the Harem.

- The Sultan and the Queen Mother had ornate sleeping quarters.

- Sitting rooms were located throughout the palace.

- This beautiful copper chimney kept somebody warm during Istanbul’s cold winters. Yes, it can snow in Istanbul.

- Many of the small chambers had these charcoal burning pots as heaters.

- Stained glass windows throughout the palace were truly amazing.

- This couple decided to take a nap. We probably should have followed their example.

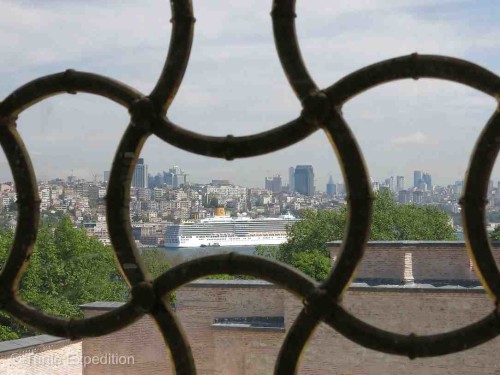

- The view from the higher balconies of Topkapı Palace overlooking the Bosporus and entrance to the Golden Horn was spectacular.