Okay, we were now driving in Turkmenistan. Oh Boy! It had been a long night and a long frustrating day. Since our five-day transit visa had already expired we were essentially driving in the country illegally. We knew that fuel in Turkmenistan was a dollar a gallon. Even though we had to pay $100 fuel surcharge, we had arrived with empty tanks. After a quick drive around town to change money we found the only gas station had run out of diesel. Thinking there must be other stations outside of town, we headed for Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, some 324 miles away. After driving 20 miles into the barren desert, there was nothing but ugly sand dunes and scrawny camels. We stopped at a construction camp to see if they had any diesel. They didn’t, but they said there was a station another 20 miles or so down the road. We had no choice. With the fuel needles resting past the red mark, we pulled into Belek on fumes and filled both of our Transfer Flow tanks to the top, a total of 84 gallons. That would give us an easy range of almost a thousand miles, enough to reach the border of Uzbekistan.

The heat next to “the Door to Hell” in Turkmenistan was intense.

Stopping in the little town of Serdar, we found a safe place for the night in a small park. The local people were friendly but we had little time to visit. Early morning, we walked around to get a feeling for the locals. One house had some ribbons and decorations for a wedding or perhaps a birthday. If we had stayed I’m sure we would’ve been invited. Monika passed one older gentleman working in his garden and he offered her his first cucumber as a present. This is a very Muslim country. A good friend in Istanbul told us that one interpretation of the Koran requires women to cover all of their personal features. The two girls that passed us in their chic dresses left little to the imagination of how beautiful they were.

Getting an early start the next morning, we more or less blitzed the capital of Ashgabat. It had that tinsel look of an overgrown Las Vegas wedding chapel. Having seen the obvious third world poverty in the little town where we had spent the night, it was pretty obvious where the money the government was raking in was going, and it wasn’t to the people. The massive building projects outside of town reminded us of the “phantom” apartments being constructed in China. No sign of anyone living nearby.

We sought refuge behind a hill to escape the additional heat source of “The Door to Hell”. It was still around 140F!

The Karakum Desert encompasses over 70% of Turkmenistan, about 135,135 square miles, (350,000 square km). Reported to be the hottest desert in Central Asia, it may also be in the running for the least appealing. We drove north on marginally OK pavement but some sections pocked with bathtub size potholes kept our speed below 30 mph most of the time. Work was ongoing but overloaded trucks and the extreme heat had created a rollercoaster effect on the melting blacktop. Our only stop was to buy a fresh watermelon from a young roadside vender.

To keep the desert sand from completely obliterating the road, huge sand barriers had been constructed from bunches of reeds sewn together and partially buried in the sand. About 160 miles north of Ashgabat we came to the area that was supposed to be the village of Darvaza. Its inhabitants, 350 of them, were mostly Turkmen of the Teke tribe, preserving a semi-nomadic lifestyle. In 2004, the village was disbanded following the order of the President of Turkmenistan, Saparmurat Niyazov, because “it was an unpleasant sight for tourists”.

Camping behind a hill by “The Door to Hell” we were somewhat sheltered from the heat and the fumes.

In 1971 when the republic was still part of the Soviet Union, a group of Soviet geologists went to the Karakum in search of oil. They found what they thought to be a substantial oil field and began drilling. Unfortunately for the scientists, they were drilling on top of a cavernous pocket of natural gas which couldn’t support the weight of their equipment. When it collapsed a crater about 230-feet across and 65-feet deep was formed. (40° 15’ 10” N 58° 26’ 22” E).

Natural gas is composed mostly of methane, which, though not toxic, does displace oxygen, making it difficult to breathe. This wasn’t so much an issue for the scientists, but for the animals that call the Karakum Desert home — shortly after the collapse, animals roaming the area began to die. The escaping methane also posed dangers due to its flammability — there needs to be just five percent methane in the air for an explosion to potentially take place. So, the scientists decided to light the crater on fire, hoping that all the dangerous natural gas would burn away in a few weeks’ time. Now, 46 years later, it’s still burning! It has since acquired the name of “The Door to Hell” or “The Gates of Hell”. (Check out our YouTube link below the photo gallery) Aside from the occasional tourist, reports say that it also attracts nearby desert wildlife. Some attest to seeing local spiders plunging into the pit by the thousands, lured to their deaths by the glowing flames.

All along the road through the Karakum desert were these hand planted traps to keep the roads clear from drifting sand.

Apparently the Turkmenistan government doesn’t really like people visiting the crater. There is no sign for the entry to the well-used two-track. The sand was very soft so we locked the hubs. After about a half an hour we climbed over a final sand dune where we could see the pit. The temperature was oppressive, about 140°F near the edge. We didn’t drive too close, not knowing how strong the overhanging lip was. We did inspect on foot to see if any friends or relatives who don’t read our blogs were hanging by their fingertips.

Wanting to see the crater by night we drove behind a nearby hill thinking the heat would be less. Nighttime came and the temperature dropped to 130°F. Even with damp towels laying over us and both Fantastic-Vent fans on high, sleep was miserable. We ended up starting the engine and sleeping in the cab with the AC on high.

One could easily understand why they placed these sand traps along the road.

Driving out the next morning was more challenging than expected, more uphill than I had remembered. We should have aired the tires down to 20psi but I was reluctant to the task of airing them back up after only a few miles to the pavement. I locked the front ARB differential and let the TrueTrac limited slip in the rear do its best with a few hops and clunks as we struggled up through the soft sand. As always, the situation was too tense to take any pictures. This was no weather to get stuck in and there was not a tree or winch point for miles. Back on terra firma, we took a deep breath and turned north toward the border, 77 miles away, hoping it would still be open. It wasn’t.

We had not seen a fuel station on the highway since we left Ashgabat. Apparently there was only one. A taxi driver offered to show us the way. We topped up both tanks and filled the two auxiliary jerry cans. Returning to the border, we camped as close to the entry as possible, just next to a cute café. There was a party going on and we were quickly invited.

Morning came and the trouble started. Our 5-day transit visa had expired and the fact that the ferry was 4 days late made no difference. We had to return to the local immigration office in town to get a new visa or exit permit paper. (This government loves paper work!)

As the sun set the hill behind “The Door to Hell” started to glow.

To make a long story short, we had two choices. Pay a $380 fine each for being in the country illegally, or fill out a letter of explanation in long hand, (two copies), explaining why, and then be deported with the stipulation that we could not reenter Turkmenistan for five years. We wanted to say, “Great!!! Make it 10 years!”

More problems! Of course, the border was closed for their 2-hour lunch. Another hour of paper work. A $25 fee for what we didn’t know, and finally an inspection of the camper, (We were leaving, remember?), and oh by the way, it was illegal to exit the country with any auxiliary cans of fuel. Thank goodness we had filled our two Transfer Flow tanks. Still, we had to empty the jerry cans. I was so pissed I was ready to dump them on the ground, and oh, by the way, our truck could not leave the Customs compound. In the sweltering heat, Monika and I lugged the two 5-gallon cans 200 yards across the baking concrete and out the gate, and just by sheer chance, of course, the guy with the taxi had a big drum in his trunk and he generously offered to dispose of the 10 gallons of diesel.

The sunset at “The Door to Hell” in Turkmenistan was spectacular.

We stormed back with the empty cans and I was rapidly turning into the “Ugly American”. Can I blame the heat? Monika demanded to see the written law that said we could not leave the country with full external fuel cans. They showed it to her. All she could read was “saliarca”, the Russian word for diesel. Now the agent, who was enjoying being an asshole, wanted to know what was in the blue jerry cans. I said “water asshole, wanna see?” Knowing that the cans were very full and the outside temperature was still over 110°F, I made sure he was very close when I flipped open the sealed cap, which exploded with hot water in his face. I said “See asshole? Water!! Want to see the other one?” He didn’t. (Monika took over quickly as I was close to getting into real trouble due to my choice of words.)

We left with a couple of good blasts of our twin air horns as we passed the last guarded gate where another diligent guard carefully inspected all our papers—like we could have gotten this far without them. Good-by Turkmenistan!

-

-

After driving 20 miles into the desert, there was nothing but scrawny camels.

-

-

-

-

-

In the little town of Serdar we found a safe place for the night in a small park.

-

-

-

-

The town had that exSoviet look of a third world country. Check out the water supply on the side of the truck.

-

-

-

People seemed friendly.

-

-

This gentleman offered Monika the first cucumber from his small garden.

-

-

There were signs of an impending wedding or birthday party. We wished we could have stayed another day.

-

-

Note on the far right there is an LP tank that feeds the cooking pot and the hot water heater on the far left.

-

-

Properly dressed in Muslim tradition, but leaving no doubt how beautiful they were.

-

-

-

-

Long rows of building projects outside of Ashgabat reminded us of the “phantom” apartments being constructed in China.

-

-

Monuments like these showed where the government’s money was going.

-

-

-

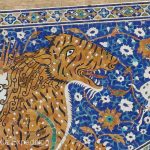

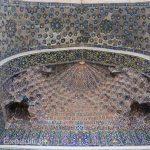

With more time, we would have liked to visit this beautiful mosque.

-

-

Sign of the times, this old Russian bus was started with a hand crank.

-

-

Some pavement was OK but other sections were pocked with bathtub size potholes that kept our speed below 30 mph most of the time.

-

-

-

Overloaded trucks and the extreme heat had created a rollercoaster effect on the melting blacktop.

-

-

-

Road construction was going on but it could be years.

-

-

-

Close inspection shows a classic Russian twin cylinder with a sidecar.

-

-

Our only stop was to buy a fresh watermelon from a young roadside vender.

-

-

-

-

Arriving at “The Door to Hell”, the temperature was about 140°F. We dared not to drive any closer to the edge.

-

-

-

The “The Door to Hell” was most impressive from dusk to dawn. We saw no signs of friends or relatives clinging to the edge.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Camping behind a hill did not let us escape the heat of the desert, said to be the hottest in Central Asia.

-

-

-

-

We stopped to unlock the hubs and headed for the border.

-

-

To keep the desert sand from completely obliterating the road, huge sand barriers had been constructed from bunches of reeds sewn together and partially buried in the sand.

-

-

-

-

-

The highway seemed to get progressively worse as we drove north.

-

Click on this link to see our “Gate to Hell” video on YouTube.