Ferghana Valley, Uzbekistan – July 2014

If you had been herding a string of stinky smelly ornery camels over the desolate nearly impossible high passes of the Pamir Mountains through Tajikistan, or the Qurama Mountains out of Kyrgyzstan, the fertile Ferghana Valley would have been a welcome sight. Silk Road caravans would find ample grazing for their animals across the flood plain of the Syr Darya River that twists its way for nearly 200 miles. This had been the breeding ground for the legendary Dragon Horses, the blood-sweating steeds renowned for their great size and speed. Well, they didn’t actually sweat blood, but the warriors of Genghis Khan are reported to have ridden day and night while making small slits in their horses’ necks to drink their blood.

We had just parked when this young girl, her brother and his friend arrived to welcome us with a bowl of fruit.

Leaving the relatively comfortable air-conditioned environment of the last hotel room we would stay in for months, we left Samarqand and headed northeast towards Jizzakh on M39. Traffic was varied from typical third world style to absurd. Not being too concerned about our camels, finding a place to camp for the night was simply a matter of turning off on a side road, driving over the hill to find a grassy spot. On this particular evening, we were joined by a small herd of fat tail sheep that have always fascinated us.

In places highway construction was obviously underway but we had to wonder about the huge amount of manual labor it took to cover the unfinished roadway with plastic, held down by carefully placed rocks, one rock at a time. This region was famous for its melons and there were plenty of road side stands to tempt us. We had no reason to visit the busy capital of Tashkent, so we stayed to the south on secondary roads.

FERGHANA VALLEY

Keeping an eye on our Auto Meter mechanical gauges we climbed a long series of steep switchbacks out of a deep canyon into the Qurama Mountains and over the Kamchik Pass, 7,441 ft., (2267 m). The pass has long been a strategically important trade route between the Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, bypassing neighboring Tajikistan. Circling back south, we bypassed the city of Qoqand to reach the town of Rishtan, home of the ceramic workshop of the father-and-son team of Rustam and Damir Usmantov. Looking for a quiet place to camp for the night, we saw a large vacant lot behind a small weekend market and store. The gentleman who owned the store assured us there was no problem spending the night. No sooner had we parked that a young girl arrived to welcome us with a bowl of fruit. We ended up taking pictures of her family. It didn’t take long for friends and neighbors to find out. They too showed up with their own welcome gifts so we printed photos for all of them. In the past we had always carried a polaroid camera and but now we carry a small printer in the truck. They were as delighted as we were.

RISHTAN CERAMICS

The Usmanov family migrated to Rishtan from Russia to add to the region’s rich tradition of pottery. The beauty of the Rishtan ceramics is the ishkor glaze which gives it its brilliant blue-green sheen, bringing alive the colors of the earth and the sky. Of course, we couldn’t resist bringing home a couple samples.

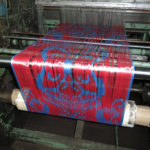

Continuing on a loop, we headed towards the town of Marghilan, famous for its silk factories. Marghilan is one of the most ancient cities of Uzbekistan. It was well known already in antiquity because it produced the best silk in Central Asia, able to compete in quality and beauty with that of the Chinese. Caravans with Marghilan silk traveled along the Silk Road to Kashgar, Bagdad, the Khorasan region and all the way to Greece.

MARGHILAN SILK

We were fascinated with the exquisite patterns the weavers at the Yodgorlik” Marghilan Factory produced.

The unique Uzbek Khan-Atlas silk fabric is almost completely handmade. For hundreds of years the Ferghana masters managed to develop their own technique and technology of tie dying thread and weaving it into beautiful cloth, from a cocoon to the finished product, which makes the Marghilan silk one of the best in the world. The “Yodgorlik” Marghilan Factory may be the only one that has preserved a manual method of silk production. During a very educational tour we were able to see the whole silk manufacturing process, ending with tea and a visit to their showroom where visitors can buy various silk fabrics and mixed-silk fabrics.

Spending a little time wandering around the town of Marghilan, we smiled at the long overhanging canopies of grape vines that shaded sidewalks in front of homes. Roadsides were lined with mulberry trees to provided food for the all-important silkworms. More than in any other town we had seen in Uzbekistan, the art of making fresh bread had reached its pinnacle.

There were several bakeries in town, each with its own unique design of obi-non, the circular local bread. Right across from the Yodgorlik Marghilan Showroom a friendly baker was just in the process of scooping the wonderfully smelling obi-non out of the hot oven with his long handled pan. He was happy to let us peak into the oven and take photos. With a warm loaf in hand, we walked straight to the truck to enjoy a piece with butter.

Heading back west, we camped near the border crossing into Tajikistan. What we had to fear now was the infamous Tunnel of Death. As one overland traveler had recently posted:

The Tunnel of Death, Tajikistan

Visibility reduced almost to zero thanks to large sections with no lighting. Useless headlights which fail to penetrate the fumes. Carbon monoxide accumulation which has already claimed the lives of people delayed in the tunnel. All vehicles must have windows up and airflow on recycle. Potholes which seriously challenged ex-military trucks in permanent 4WD. Exposed reinforcing bars in the remaining concrete road surface had punctured the tires of 2 trucks whose drivers were changing them in the tunnel. Along the length of a mid-tunnel section there are holes as deep as 1.5 meters which are full of water. No roadworks signs and no traffic controls in this single-lane section or anywhere else.

Sounds like fun huh?

- Traffic was varied from third world style to absurd.

- Who needs a moving truck?!

- Road repair just happens. We don’t need no stink’n signs.

- We had to wonder about the huge amount of manual labor it took to cover the unfinished roadway with plastic, held down by carefully placed rocks, one rock at a time.

- Who needs a tree for a nest? It was fun to see the storks, a childhood memory for Monika.

- Turning off on a side road and driving over the hill, we found a grassy spot to camp.

- We were joined by a small herd of fat tail sheep that have always fascinated us.

- We were amazed to discover a Chicory plant in this part of the world.

- This region was famous for its melons and there were plenty of roadside stands to tempt us. Everyone welcomed us.

- Throughout the ex-Soviet region many people wear gold teeth.

- Keeping an eye on our Auto Meter mechanical gauges, (www.autometer.com), we climbed a long series of steep switchbacks out of a deep canyon into the Qurama Mountains and over the Kamchik Pass, 7,441 ft., (2267 m).

- Our Garmin GPS gave us a birds-eye view of the road over Kamchik Pass.

- We had just parked when this young girl, her brother and his friend arrived to welcome us with a bowl of fruit.

- Over the course of a couple hours, word spread in the neighborhood and many kids, mothers and grandmothers arrived with welcome gifts.

- This gentleman invited us to park on the weekend market property for the night.

- Once we found the address, the home of the ceramic workshop of the father-and-son team of Rustam and Damir Usmanov was unmistakable.

- The beauty of the Rishtan ceramics is the ishkor glaze that gives Rishtan pottery its brilliant blue-green colors of the earth and the sky.

- The Usmanov family had migrated from Russia to Rishtan to add to the region’s rich tradition of pottery.

- Each beautiful piece of ceramic is a hand-painted work of art.

- Finished pieces are glazed and fired in a small oven.

- It took Monika a long time to settle on these three pieces to take home.

- Long overhanging canopies of grape vines shaded sidewalks in front of homes.

- Roadsides were lined with mulberry trees to provided food for the all-important silkworms.

- The little fuzzy silkworm cocoon is where it all starts.

- The Yodgorlik Marghilan Factory may be the only one that has preserved a manual method of silk production.

- Gary is inspecting a hand powered hank winder.

- Washed and dried, the fine silk hanks are ready to be dyed.

- The unique Uzbek Khan-Atlas silk is famous for its beautiful natural dyes and brilliant colors.

- The hanks of dyed silk are hung to dry.

- The dye bath is ready for the next batch.

- The tied silk threads are sitting in a hot dye bath for quite some time.

- Individual lengths of silk thread are tightly wrapped in sections before being dyed to produce the beautiful tie-dye effect.

- Strands of tie dyed silk thread is ready for the next step.

- It was interesting to see how many different hands touch the silk before it even makes it to the loom.

- Teamwork. The girl on the right holding a hank of silk thread assists the other girl winding a ball.

- These bobbins are ready to be used.

- The lady inserts a bobbin into a boat shuttle she’ll use for the weft on her loom.

- This lady is setting up her loom. The warp strands are still tied together.

- Though some of the weaving is done on machines much of the beautiful silk patterns are still woven on the old fashion handlooms.

- Slowly but surely the unique Marghilan silk pattern emerges.

- After seeing how these beautiful silk fabrics were made, the factory store was a great place to do some shopping.

- Monika was tempted to buy several Marghilan silk fabrics.

- This interesting hand-carved pillar in the factory store caught our attention.

- Reconditioned baby carriages seemed to be a practical way of hawking fresh obi-non (bread) from the oven.

- We poked our heads into one of the bakeries for a firsthand look at how the delicious bread was made.

- When the dough is shaped, each piece is individually slapped onto the wall and ceiling of the oven until it is baked to a golden brown.

- The baker is scooping the golden obi-non (bread) out of the hot oven.

- The freshly baked obi-non are ready for sale.

- Each obi-non bakery had its own signature design.

- This baker demonstrated how he scoops the hot obi-non out of the oven.

- This young family asked if they could see the inside of our home.

- Hot dog, hamburger, cheeseburger and a coffee, what else do you want?