Introduction

The Russian Adventure

An Introduction

The Turtle Expedition Team

Gary Wescott studied photography and journalism at the University of San Diego, and began traveling in 1969. He created The Turtle Expedition, Unltd. in 1972. Since then, his photographs and articles have been published in fifteen countries in ten languages on six continents. His unique style has drawn the praises and a loyal following of four-wheel drive and travel enthusiasts around the World.

Monika Mühlebach Wescott was raised and educated in Switzerland, graduating from the University of Zürich with a degree in teaching. Joining The Turtle Expedition in 1977, she began to develop her skill as a photographer and editor. Speaking five languages fluently has helped to open doors wherever The Turtle Expedition goes.

An Idea—-The Problems

The Turtle Expedition’s logo has become synonymous with travel and adventure during the past 28 years of Gary & Monika’s endless Odyssey around the World.

In the beginning, it was innocent enough.The idea to drive across Russia had lurked in the back of our minds since my participation in the 1990 Camel Trophy. The Turtle Expedition, Unltd. has always been fascinated by extremes. Now, there was Russia! One sixth of the Earth’s surface!! Eight million square miles; 7,000 miles across eleven time zones stretching halfway around the planet! Russia is 2 1/2 times larger than the U.S.! Her doors were now suddenly, and perhaps only temporarily, thrown open to adventurers for the first time in over seventy years. Could this unique opportunity be missed??

A year of research and preparation had served only to show us how unprepared we were, uncovering many unsolved problems which lay ahead. For starters, there was no all-weather road across the Russian Far East, (East Siberia). A vast wilderness of forest and swamps in the South stretches north across unbridged rivers, high mountains, and frozen tundra to the distant shores of the Arctic Ocean. We could find few foreigners or Russians who had ever crossed Siberia with a vehicle, and those who had invariably resorted to the Trans-Siberian Railway in the South, with its Pacific terminus in Vladivostok, or the BAM Railway from Tynda. Other routes involved the use of river barges for hundreds of miles, down the Aldan from Khandyga and up the mighty Lena to Ust Kut.

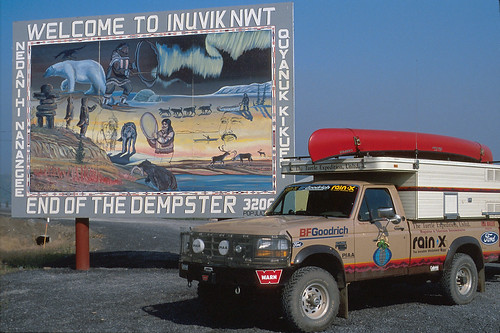

Crossing the Arctic Circle for the fourth time in a month, we returned from Prudhoe Bay with answers to many cold-weather problems.

At the end of the Dempster Highway, and later in Prudhoe Bay, we searched for cold-weather problems and their answers. The Dempster and the Haul Road are the most northern roads in North America.

It seemed to us, that using trains and barges just because there’s no easy road,—other than simply to get across unbridged rivers or oceans,— is like using a helicopter to climb a mountain. That brought us to the only possible answer: Winter Roads.

Winter Roads are not a new invention. Russian Cossacks and trappers, and before them, the Paleo-Siberian and Altaic tribes, including the warriors of Genghis Khan and the Tatars, roamed the forests and valleys of Siberia for milennia, following these frozen tracks.

There were few places to really test most of our Winter equipment. We traveled to Utah looking for some cold weather and deep snow.

Even in Cold Foot, Alaska, on our way to Dead Horse and Prudhoe Bay, we found mild temperatures compared to what Siberia would hold for us.

We began to realize that if we were to actually drive across Russia, timing would be critical. Winter comes early in the Far East. A September snow is normal, and major rivers freeze in November, when the inland mountains and valleys begin to suffer some of the coldest temperatures in the World. If the average is minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (-40°C), weeks can pass when the mercury never climbs above -60°F! There are documented lows below -100°F!! At sixty below zero, metal can crystallize and snap, and plastics—like photographic film and the vinyl sides of our Four Wheel pop-up camper—can become as brittle as a potato chip. Tires and fan belts can freeze and crack like glass and a 5-15W Arctic oil turns to heavy jello. Gear oil becomes solid.

Avalanche Danger was posted on the well-traveled Haul Road. In Siberia, such dangers would be taken for granted.

The Haul Road was dusty when it got cold enough to freeze all moisture. Flying gravel prompted us to design a windshield rock guard for The Turtle IV. Siberia was not a place to break a windshield.

Our own safety was of paramount concern. The human body, with its built-in internal heater, is far easier than a truck to keep alive in such extremes, but frostbite can occur in minutes at temperatures below -50°F. Our Northern Outfitters Expedition Series EXP II Clothing Systems would protect us down to -100°F in a worst-case scenario.

Fuel could be a problem. Normal diesel turns to syrup at -60°F, clogging filters with globs of wax and reducing fuel lines to mere capillaries. That’s if we could find fuel, which was reported to be in short supply throughout Eastern Siberia. Our support trailer’s auxiliary tanks, filled with high-grade jet fuel before we left, would give us a range of over 1,600 miles. Racor, Motorcraft, and Cim-Tek Hydrosorb fuel filters and heaters would keep dirt and water out of the injection pump and, in combination with Red Line Diesel additives, keep the fuel in a liquid state, we hoped!

Food?!! Following a reconnaissance trip to Central Siberia in January of 1995, we were told by Russians and foreigners alike that food could be scarce, and locals in villages might have barely enough to last the Winter. Basic supplies like butter, milk, rice, beans and pastas must be brought with us. Fresh fruit and vegetables were unheard of in winter months. Our support trailer would allow us to carry at least ninety days of basic dry goods, canned meats, and AlpineAire freeze dried vegetables.

Deep unbridged rivers were one reason why we had to cross Eastern Siberia in the Winter. The Camel Trophy had taught us some valuable lessons.

Water—when it could be found in liquid form—needed to be boiled or filtered. Some people recommend both. During the coldest months, we could not use the camper’s water storage tank with its Everpure purification system. One-liter Nalgene containers would be carried inside the camper, and a portable PUR water purifier would to be used. The PUR Explorer with its Tri-Iodine Resin Filter, will kill viruses, our main concern.

Cooking and heating in our Four Wheel pop-up camper would be interesting, starting with the fact that propane freezes at -42°F. In any case, the nearest propane fill depot we knew existed thousands of miles west of our starting point. Multi-Fuel Coleman Peak I Apex II stoves would serve as a back-up for cooking and melting snow.

Bottomless mud in the Siberian permafrost was something we had to avoid with our heavy vehicle. In Winter, these roads are frozen, and our adventure was not a Camel Trophy, with multiple vehicles and helicopter support. We traveled alone.

Tests in Prudhoe Bay in 1994 showed a bottle of propane would keep the three-season camper above freezing for only four days at a balmy eighteen degrees above zero Fahrenheit. A Hunter Falconaire DH-22 20,000 BTU diesel-fueled heater replaced the factory propane unit. Additionally, a Hunter HW-6 123V variable 6,000 to 20,000 BTU hot water heater, plumbed to the engine’s cooling system, was installed.

Russian medical facilities, a reported 40% of which do not have hot running water, were not recommended. Inoculations for travel in Russia’s backcountry read like the Who’s Who list of life-threatening diseases, including cholera, typhoid, rabies, hepatitis A & B, Japanese encephalitis, tetanus/diphtheria, polio, and Russian Spring tick fever. We had to be self-contained, careful, and lucky. Especially in remote areas, our ability to contact the outside world would be virtually impossible. Hughes supplied us with a briefcase MagnaPhone Satellite Communication System for use in an emergency situation. Using our Lowrance GPS, we would know our exact location. We studied wilderness first-aid books and practiced sewing sutures on an orange.

All these problems notwithstanding, there were the ongoing horror stories of bandits, highway robbery, Mafia, and rising crime. Reports from both the American Embassy and Russian & American contacts inside the former Soviet Union indicated that these dangers were real and should not be taken lightly. It was suggested that we travel armed and most certainly not alone, least we end up in a ditch with a bullet in the back of our head.

You should be getting the picture. This was not going to be a “drive in the country”. Simply discovering how to get our expedition truck and its support trailer to Magadan was a challenge. (The first “expert” advice we received from the office of Russian-American Commerce in Alaska was to “hitch a ride” from Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians on a passing Russian fishing boat.)