Baja Testing The Turtle V (Visiting Whales, Caves & Old Ranches)

BAJA TESTING THE TURTLE V

Nothing is Bulletproof

Author: Gary Wescott / Photos: Gary & Monika Wescott

No one likes to break, especially if you drive a Power Stroke Super Duty F-550 like The Turtle V. This is the pick-up of all pick-ups, right? Beefed up frame and brakes, monster Dana 135s differential, heavy-duty suspension all around, and in our case, the ultra reliable 7.3 L engine. But then, every mechanical device has its limit, and when it is reached, it’s frustrating.

Steep narrow sections of the trail to the abandoned Guadalupe Mission had been cemented in. Other parts required 4×4 to avoid spinning tires.

As The Turtle Expedition prepares for our next major adventure, the Trans Eurasian Expedition, traveling from Lisbon, Portugal to Bejing, China, through 26 countries, some with rather uncertain political and road conditions, we will certainly rely on our Ford Super Duty for safe transportation and safe haven.

Our rustic camp at Los Petates in San Ignacio was relaxing. Bullfrogs in the lagoon serenaded us every night.

It’s not that we go out and try to break things, but with over 120,000 miles on The Turtle V, many of them on rough, marginally improved backroads in the U.S., Baja California, and mainland Mexico, there have been problems.

Our transfer case went south at about 25,000 miles for no apparent reason. Ford replaced it. Two of the front wheel sealed unit-bearings failed. The permanent fix was the Dynatrac Free-Spin replacement serviceable bearing kit. A water pump leak was covered under warranty. The Ford clutch destroyed itself at about 71,000 miles. A South Bend replacement unit was detailed in the Fall 2006 issue of PSR (Power Stroke Registry).

Both front and rear camper mounting points failed due to poor engineering by a now-defunct company in Canada. The BIGFOOT 4×4, Inc. shop in St. Louis, Missouri redesigned the rear pivot mount, making it much stronger. When the front mounts failed, also obviously under designed, Browns Valley Truck and RV Performance Center replaced them with thicker extruded industrial steel and added more bolts and gussets.

The narrow two-track leading to the abandoned Guadalupe Mission left its share of mesquite branches and scratches on The Turtle V.

Cabinet latches have cracked and were replaced with stainless marine-quality Southco hardware. All drawers were rebuilt with glue and screws to replace the staples. A rear leaf spring broke in Baja. We limped back to El Cajon, CA, where National Spring added full military wraps. We installed Hellwig Air Suspension in the rear to soften the ride. Three out of four anti-sway bar brackets broke and were re-engineered.

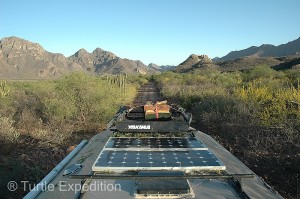

Admittedly, we follow some pretty rough backroads, but part of preparing an expedition vehicle is to put some miles on it so you can improve its reliability before you leave the safety of civilization and easy access to parts. Baja is a great testing ground.

We recently headed south of the Border to research some stories for magazines and to visit some areas we had never explored. Traveling alone for a change, without a tour group trailing along behind, we had the freedom to follow our motto, “Don’t take the trip. Let the trip take you!” We did make time to research a new possible route for a future Backroad Adventure.

Our adventures took us from Ensenada near the California border, down the inland spine of the peninsula, across to the Pacific, back over the mountains to the Sea of Cortez, back again to the abalone fishing villages of the Pacific, and finally, up the rugged coast of the Sea of Cortez, over 4,000 miles, following some of the worst trails we have ever encountered. Along the way we had some great experiences, and some not so great.

Our first stop was Laguna San Ignacio to see the Giant Gray Whales, which migrate there every Winter by the hundreds to calve and mate. We were fortunate to find one of the oldest and most whale-friendly whale sighting camps on the lagoon. Pachico’s Eco Tours is run by Jesus Mayoral. His father, Pachico Mayoral, was the first person to actually make contact with the whales over 36 years ago.

It is quite an amazing experience to be within two feet,–eye-to-eye contact–, with one of the largest creatures on Earth.

Great care is taken in Laguna San Ignacio not to disturb these giant mammals. As we patiently waited in our panga, the motor quietly idling, several mothers came to visit. They would first surface to see who it was, then come closer for a gentle pat on the head, and finally, nudge their baby caves up to the boat so we could pet them too. We did have one big male visit. He rolled on his back, drifted under the boat, breached a couple of times, came up for a quick pet, and as if to say goodbye, gave the panga a little bump as he swam away.

It is quite an amazing experience to be within two feet,–eye-to-eye contact,— of one of the largest creatures on earth. They can reach a length of 45 feet and weigh 40 tons. By April, most of the males have left, and by May, the calves are strong enough to follow their moms back north to Alaskan waters, some 5,000 miles away.

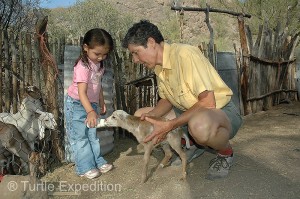

Over the years, we have spent more time in Baja California Norte than Baja Sur, but I recalled being told about a small fishing village south of Loreto on the Sea of Cortez called Agua Verde. I had also heard that the locals raised goats, and could, for a small fee, butcher one and prepare it for you.

Huge “fish boils” happened, right in front of camp, with hundreds of pelicans and other sea birds in a feeding frenzy.

The dirt track over the mountains was in decent shape, but not for anyone with a fear of heights. Nothing much bigger than a van or pick-up normally follows it. The little bay was idyllic. We pulled out to the high tide mark and set up camp. The village has neither electricity nor phones. Water is piped in a few hours a day from a spring up one of the canyons. Fish were plentiful right off the shore. We saw “fish boils” frequently, right in front of camp, with hundreds of pelicans and other sea birds in a feeding frenzy.

This tire was obviously way beyond any repair. That left us with 1,000 miles of backroads to drive and no spare.

Yes, there were goats. We bought two for $30.00, and they were prepared in a delicious spicy red stew called “birria de chivo”, famous all over Mexico. For our small investment, family and neighbors were invited to the feast, which fed over 20 people.

Back on the pavement, we aired up the tires and headed north toward Mulegé. Then it happened. The explosion rattled the windows, and the right rear of the truck dropped like a rock. What the hell!!! The rear tire had blown out as if it had a bomb inside. The SmarTire pressure sensor on the dash still read “57 psi”. It happened that fast. No warning. I limped to the side of the road. Mexican highways generally do not have shoulders of any kind. By sheer luck, there was a flat area on the left about 100 yards ahead. With no choice, I limped forward at 2 mph. The force of the explosion ripped off the rear Bushwacker fender flare and took most of the wheel well coating off.

The good news is, we had a spare, and all the tools to change a 130 lb. tire. Just two minutes further and we would have been on a steep five-mile set of narrow switchbacks with no turnouts and big semi trucks coming in both directions.

Hotel Serenidad outside of Mulegé is where Monika and I actually first met nearly 31 years ago. It was time for a Tequila Sunrise!

It was Saturday when we arrived at Hotel Serenidad outside of Mulegé, and the weekly roast pig on a spit feast was our rewards for a difficult day.

Catching our breath, we continued on to the old Hotel Serenidad outside of Mulegé where Monika and I actually first met and decided to travel together, nearly 31 years ago. Again by luck, it was a Saturday night; the weekly roast pig on a spit feast was our reward for a difficult day. Even after all those years, Don Johnson and his wife, Nancy, owners of Serenidad, remembered Monika and invited us to sit at their table.

Crawling under the truck for a general inspection the next morning, we saw another little problem. There was a crack in the frame just opposite the factory cutout for rear shock absorber clearance. This was not good! Though we do carry a Ready Welder wire-feed welding kit, we had a “professional” at a local shop put a patch over the crack. It broke again two days later.

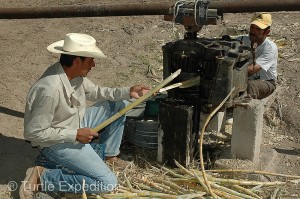

Admittedly, I was a little nervous, driving backroads in the middle of Baja with no spare tire and a cracked frame, but we had places to go and people to see—sort of. One of the guys working at Pachico’s Eco Tours had invited us to visit his ranch to watch the annual sugarcane pressing. Sugarcane in Baja?

Many of these remote ranches were originally founded by the Jesuits in the 1700’s during the settlement of Baja, and later by the Franciscans and Dominicans. These isolated oasises are often days apart by mule. The introduction of roads and pick-ups have made life easier, though there is still no electricity except for small solar panels, and in most cases, nothing you could call running water. Cooking is done primarily on wood stoves. VHF radios keep neighbors informed of the news. Fields are plowed with a mule or by hand, and much of the everyday activity has not changed for over 100 years. Never mind that there is an old Ford F-150 with two flat tires sitting under a mesquite tree in the yard. It may not run.

Patrocinio was one of the original mission ranches established during the time of the Jesuits. Thirty-two miles of washboard through the desert brought us to the oasis where a natural spring bubbles out of an old riverbed. There were four ranches in this valley, and large groves of oranges, pomegranates, figs, dates, and a small patch of sugarcane. Our friend, Ramón Aguilar, met us with open arms and gave us the red carpet tour. Lack of electricity and running water were easily compensated by the warm hospitality typical of these remote historic ranches.

Date palms introduced by the Jesuits are common wherever there is an oasis. Ripe dates hang from trees ready to be tasted.

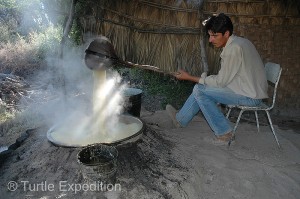

Monika is caught sneaking a taste of the still-warm panocha. At this stage of its all-day process, it looked like creamy peanut butter.

Extracting the juice of sugarcane was done on a press made by Blymyer Iron Works in 1892. A mule powered it. The juice was then boiled in a huge bronze kettle for 5 hours, with constant stirring. Then it was cooled for another hour and a half until it began to thicken to a constancy of creamy peanut butter. Finally, it was poured into molds to fully harden. The result is a very sweet soft candy called panocha, which has a slight caramel flavor. The mesquite mold used at Patrocinio was over 114 years old.

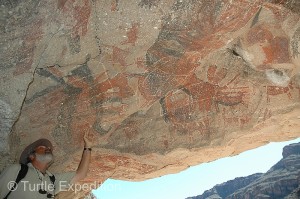

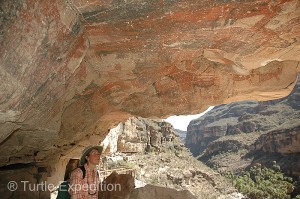

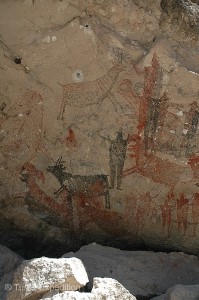

Returning to San Ignacio, we ventured into the rugged San Francisco Mountains. Deep in these remote canyons, some 10,800 years ago, prehistoric people scaled cliffs, and for reasons still not clear, painted hundreds of caves with images of men, women, deer, whales, birds and artistic designs. The caves were declared a World Heritage Site in 1993, and today, you must have a local guide to see them.

Twenty-nine miles of gravel washboard brought us to Rancho San Francisco de la Sierra. The frame crack was not any worse. In the morning, we loaded our backpacking gear on two sleepy burros, mounted our mules, and descended into a wilderness of nearly impassible cliffs and palisades. Six dusty hours later, we set up camp in a riverbed at the bottom of Cañón de Santa Teresa and prepared dinner for our guide, Francisco Arce, and ourselves.

A Coleman Peak 1 Multi-Fuel stove was easy to light and perfect for preparing camp food for our guide and ourselves.

The steep rocky trail into the canyon of Santa Terresa was no place for a horse. Even the mules had to be walked through some sections.

Our guide, Francisco Arce, was a classic character, but very helpful in getting in and out of the deep canyons safely.

Our 3-man MSR Mutha Hubba tent was an excellent choice for the mule trip into the deep canyons of San Francisco de la Sierra.

Water in the canyon needed to be filtered. Our MSR WaterWorks EX screwed on to Nalgene bottles and our MSR Hydromedary hydration system.

Biting flies were an annoyance. We set up our MSR Mutha Hubba in screen-tent form (we added the rain fly later) and rested our sore butts, keeping an eye on the weather. Flash floods had left debris as high as 20 feet. Groves of date palms towered over us. A small creek trickled nearby, giving us a source of water to filter with our MSR Water Works EX.

The next day was spent hiking along narrow trails to three of the most spectacular cave painting galleries in the area, Flechas, Soledad, and Cueva Pintada. The images were amazingly well preserved, considering their age. They are some of the best and oldest in the world.

The ride back up the canyon the next morning was nothing less than astonishing. We gained a real respect for mules. Horses would never survive these rocky, boulder-strewn trails. Attempting to hike these narrow paths, often no more than a foot wide with sheer drop-off, would be exhausting at best.

The ride back up the canyon the next morning was nothing less than astonishing. We gained a real respect for mules. Horses would never survive these rocky, boulder-strewn trails. Attempting to hike these narrow paths, often no more than a foot wide with sheer drop-off, would be exhausting at best.

After a well-deserved rest stop at Los Petates RV Park in San Ignacio, we headed west to the Pacific in search of fresh abalone. Years ago we had established lasting friendships with the fishermen and their families

The steep rocky trail into the canyon of Santa Teresa was no place for a horse. Even the mules had to be walked through some sections.

along this sparsely populated coast. Back then, abalone was so plentiful, it was sometimes used as bait in the lobster traps. El Niño devastated the abalone population, and today it’s called “white gold”, selling for over $65.00 a pound if you can find any.

The gravel roads from Punta Abreojos to La Bocana and up to Bahía Asunción were fast and smooth. Side roads to some of our favorite fish camps like Punta San Pablo and Puerto Nuevo now had locked gates to keep abalone poachers out. Disappointed, we continued on to Bahía Tortugas, (Turtle Bay).

The town had grown since our last visit, but our friends were waiting for us. With their help, we were able to see the laboratory at Punta Eugenia where conservation research is ongoing in a successful effort to protect and revive the abalone populations. We also took a tour of the huge processing plant where this year’s quota of 50 tons of abalone is canned for the Asian market. Despite the quantities being brought in everyday, fresh abalone is impossible to find. At over 1,200 pesos a kilo ($120), who could afford it?

Thanks to an intense conservation program and enforced harvesting limits, the abalone crop at Bahía Tortugas is thriving again.

With no spare and a cracked frame, we questioned what we were doing following these backroads. On the other hand, we were pleased that we were able to handle every problem we had encountered thus far. Nothing stopped us. It reminded us that if you’re going to explore remote areas alone, be prepared for the worst. Critical systems on The Turtle V and its Tortuga Expedition Camper; engine, transmission, drivetrain, water systems, solar and battery electrical systems;—all performed flawlessly.

That said, our adventures were not over. A few miles north of Vizcaíno, we aired our tires down for the eight time and turned east toward the distant Sea of Cortez. Bahía de los Angeles was 160 miles of dirt and dust away. Gluttons for punishment? Maybe, but if couldn’t have abalone, we needed to restock our fresh fish supply. Armed with two new 7-foot Shimano graphite poles, I knew just the place.

A healthy spring at the Patrocinio oasis is the source of life. Where there is water, there is a ranch.