Agua Verde

AGUA VERDE

Hidden Paradise on the Sea of Cortez

Author: Gary Wescott / Photos: Gary and Monika Wescott

When you spend as much time as we have following the backroads of Baja California, you hear about special places. Agua Verde had been on our mental list to visit for years. Turning off on a dirt track south of Loretto, we aired down the tires and headed west, not really knowing what to expect. But then, as I once wrote during a philosophical lapse,

“To explore child-like,

Without pre-conceived expectations;

That should be the real goal of travel.”

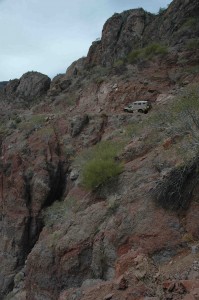

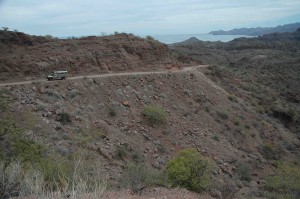

As we wound our way up and down canyons and along cliffs where the one-lane track had literally been carved out of the rock, we were amazed at the engineering invested to reach a lonely fishing village on the remote coast of the Sea of Cortez.

Each time we crested a hill, we thought, “Ahh! This must be it.” Then the road would drop down into another canyon. After an hour or so of dipping in and out of these geological corrugations, we could see the turquoise blue ocean in the distance. A long golden shoreline arched to the south. Still no village. There was no sign of Agua Verde. Climbing over another spine of volcanic rock, we dropped into a wide valley of mesquite trees, sliced by several deep arroyos. Evidence of recent floods was a good indication that you wouldn’t want to be on this track during a thunderstorm.

As we dropped over the ridge of the coastal mountains, we could see the turquoise Sea of Cortez in the distance.

We wound up and down canyons and along cliffs where the one-lane track had literally been carved out of the rock.

We were pretty sure this was a dead-end road, so we confidently continued over the next ridge, and there it was, finally, Puerto Agua Verde, a cluster of small houses scattered along a protected bay. The beach was empty except for a dozen fishing pangas pulled up on the sand.

Crossing a mesquite-studded valley, the Sea of Cortez beckoned, but there was still no sign of Agua Verde.

Children waved as we drove into town, perhaps somewhat amazed to see such a strange vehicle. Turning left at the first likely two-track to the beach, we locked the hubs and made a sweeping turn onto the soft sand, pulling up above the crest of the high tide mark. We were home, and it felt good to stop, but as it has been our practice when camping in unknown circumstances, we always leave the hubs locked and point the truck in the direction we would drive if we need to leave in a hurry.

A couple of yachts had anchored in the bay for the night. A squadron of grey pelicans skimmed the surface of the calm water above the incoming tide as it gently lapped the shore. This was a safe place. You could sense it.

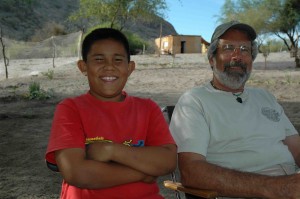

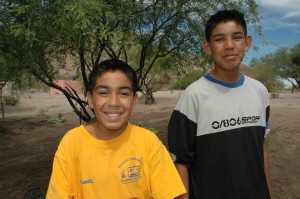

It was early evening, and our thoughts turned to fresh fish. I was just about to unpack our new Shimano poles and reels when Hugo walked up the beach. Hugo was a young boy, maybe 12. He had a smile a mile wide, and a polite way of asking were we had come from. His father was a fisherman, as most of the men in the town, and in no time we were barbequing two fresh filets of red snapper on our little Weber Go Anywhere gas grill. Our Shimanos would never see the light of day on this beach.

Hugo soon became our self-appointed guide, arranging hikes, fresh fish, and even the purchase of baby goats for a fiesta dinner.

Fish were plentiful at our Agua Verde camp. Local fishermen came in every afternoon with a fresh selection.

Camps like Agua Verde don’t come along every day, but following Baja backroads increases your chances ten fold.

Agua Verde was one of those little paradises we always hope to find at the end of a Baja backroad. While there was no electricity, phone, or Internet, (that was the good part), there was a small store, and there was water piped from a spring that ran a few hours a day. Just the warm sandy beach, clear water, and an endless supply of fresh fish would have been enough to keep us for a week, but there was more.

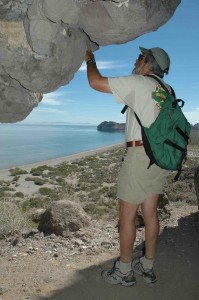

The remote mountains and canyons of Baja contain thousands of prehistoric cave paintings. The age of this unique art has been estimated at 10,800 years. Hugo and several of his friends volunteered to lead us to a nearby example, a cave with walls covered in faded designs and red handprints.

Hugo lead us to a nearby cave with walls covered in faded designs and red handprints, perhaps over 10,000 years old.

Nothing like the amazing paintings we would later visit further north in the World Heritage Site canyons of Sierra de San Francisco, but nevertheless an interesting hike. Hugo showed us a local bush with a milky sap that turned blood red when exposed to air. We could imagine how the mysterious handprints had been made.

Returning down the beach, we stopped to poke around tide pools. I questioned Hugo about a story I had heard many years ago. There were goats raised at Agua Verde; goats that one could buy and have prepared. He said he would ask his dad. Sure enough, there were a couple of herds in town, and before we knew it, we had purchased two cute little kids and made arrangements for a fiesta.

Returning down the beach, we stopped to poke around tide pools. I questioned Hugo about a story I had heard many years ago. There were goats raised at Agua Verde; goats that one could buy and have prepared. He said he would ask his dad. Sure enough, there were a couple of herds in town, and before we knew it, we had purchased two cute little kids and made arrangements for a fiesta.

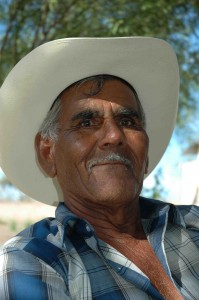

Hugo’s whole extended family took over. As loveable as the little goats were, it hurt to see them killed, but the prospect of a feast overshadowed the guilt. We are carnivores. Neighbors came with rice, salad, fresh hand-made tortillas, refried beans, and salsa. Hugo’s uncle was an expert butcher, and his mom set to work preparing the ingredients to make a delicious “Chivo in Birria”, goat meat simmered in a spicy red chili sauce, famous all over Mexico.

By the time the rich stew was ready, tables had been set and 20 people had arrived. Monika had made two of her special flans that everyone got a slice of, and there were plenty of soft drinks. Interestingly enough, no one even talked about cold beer, which made for an unusually calm party. Our total expense for the two goats was $30; a very good investment!

The dried red chilis were first toasted and then ground on a metate before being added to the goat stew.

This camp was idyllic. Hugo came to visit every day. He was an enterprising young man, still enjoying Easter Vacation from the little school in the village. While the beach was remarkably clean, the usual trash left by Mexican Easter Break campers was evident. We gave Hugo a 55-gallon plastic bag and paid him $2.00 to fill it. It was a good business, and before we left he had filled 6 bags! He was rich, and the beach was clean! The bags were disposed of in the family dump where they were burned. Not the most ecological solution, but perhaps the best alternative in this location.

Each morning, as we sat under our awning sipping our first cup of coffee, there was an astounding show going on, right in front of our camp. We had seen “fish boils” before.

A “fish boil” happens when swarms of sardines and other small bait fish are chased by larger fish, which are in turn chased by even larger fish. The water literally boils as all the fish, thousands of them, try to escape their predators. This, of course, attracts every sea bird in the area. We had seen this phenomenon further out in the ocean, but this was happening several times every morning, just ten feet from shore. Amazing! Hundreds of grey pelicans and other birds came for the easy meal. The pelicans would make their classic wings-folded-back dive-bomber entry, and surface again to dive before they could even swallow.

A “fish boil” happens when swarms of sardines and other small bait fish are chased by larger fish, which are in turn chased by even larger fish. The water literally boils as all the fish, thousands of them, try to escape their predators. This, of course, attracts every sea bird in the area. We had seen this phenomenon further out in the ocean, but this was happening several times every morning, just ten feet from shore. Amazing! Hundreds of grey pelicans and other birds came for the easy meal. The pelicans would make their classic wings-folded-back dive-bomber entry, and surface again to dive before they could even swallow.

Our visit to Agua Verde had been part of an extended 5-week test of The Turtle V and its Tortuga Expedition Camper. All systems worked perfectly. The BP solar panels kept our bank of Odyssey Extreme batteries fully charged even with the Norcold dual voltage compressor refrigerator running all day. One of the great things about the Odysseys is that their technology spans all types of batteries, deep-cell, marine and starting, so we can use the same deep-cycle batteries in the camper as the heavy-duty starting batteries in the engine compartment. Should a starting battery ever fail, we can simply take an Odyssey out of the camper and drop it in. The 2000-watt Prosine 2.0 inverter/converter gave us a reliable source of 110-volt AC power. Our water supply was adequate for a week, even with several quick hot showers. It usually took less than 20 minutes for the diesel-powered Espar D5 Hydronic to heat the water for bathing or dishes. Agua Verde had been a great camp, and one that we can recommend to anyone not afraid of narrow cliff-hanging roads. With a freezer full of fish, we reluctantly headed back to modern civilization.

Reaching Hwy 1, we aired back up. We had not traveled 20 miles when a huge explosion rocked the truck. At first I thought a propane tank had burst, but then I could feel the right rear drop a foot. Stopping safely, we surveyed the damage. The right rear tire had exploded. Our SmarTire pressure and temperature sensing system had given us no warning. In fact, it said the pressure in both rears was still a normal 57-psi. With extraordinary luck, there was a wide dirt turnout about 100 yards ahead. I gently limped across the highway, gritting my teeth as I listened to the steel rim grating on the pavement. Pulling onto a level spot, we put the spare on.

This tire was obviously way beyond any repair. That left us with 1,000 miles of backroads to drive and no spare.

Had we gone less than a quarter mile further, like 30 or 40 seconds more driving time, we would have been on a 5-mile steep windy descent with no shoulder, no turnouts, and big semi tractor-trailer trucks coming both directions. It was the 11th flat, and only the first real blowout we had experienced in 36 years of travel all over the world, so we could not be too disappointed. Now we continued, with still over 1,000 miles of backroads to follow, and the nearest spare Michelin 335/80R 20 XZL tire was sitting in a rack in Northern California. Sometimes you just have to trust luck.